Sheffield has been renowned for the quality of it's cutlery at least since the time of Chaucer. In his Canterbury Tales Chaucer mentioned that one of the pilgrims carried with him a large knife called a Sheffield 'thwitel'. At this time the pointed knife served both as a cutting utensil and as an instrument for spearing the food for putting into one's mouth when it proved too hot to handle. Usually people had two knives, one of which acted as a fork, although most often the would use their fingers for putting food into their mouths. The fork was only used for serving food.

The history of the origins of the fork is somewhat obscure. It seems to have begun its life in Byzantium and made its presence felt in the Western world when in the 11th century a Byzantine princess went to Venice to marry the Doge and took among her possessions, a fork. But the strange implement only created a scandal and gained the disapproval of the Church. It was only some five hundred years later during the Italian Renaissance which introduced several innovations that King Henry III of France noticed the strange instrument the Venetians had started using and to the idea back to France with him, where the use of the fork became widespread among his courtiers.

But progress was slow. The fork found its way to England in the possession of an English traveler, John Coryate, who had seen them being used in Italy. In Tudor times a single fork only would be included in a complete cutlery set. The early fork had two straight tines or prongs ground sharp at the points but later ones had two, three or four. Forks were variously handled, either in wood, horn or ivory and often encrusted with jewels. Queen Elizabeth I had three forks, two of them decorated with precious stones, but she still used her fingers at table for most things. It has been suggested that the use of the fork found favour in the reigns of Elizabeth and James I because its use saved the fashionable ruffs worn around the wrists from becoming soiled with the grease from the food. The fork slowly began to oust the use of the table napkin so that by the time of Charles II table napkins were simply decoratively folded into the shapes of animals and rarely used. Ben Johnson had prophesied that "the laudable use of forks brought into customer here as they are in Italy", would cause "the sparing of napkins".

And from England in 1630 the Governor of Massachusetts, John Winthrop, brought his fork and introduced the implement to America.

But the fork was becoming anglicized and in spite of the Church's opposition because of its supposed connections with the devil, the fork was in fairly widespread use by the end of the 17th Century. In the 18th Century the handles were fashionably made of agate, but by the 1750's this had given way to silver and this remained standard practice for a long time afterwards.

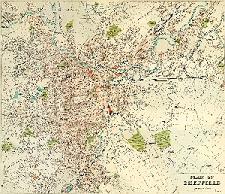

When forks began to be first manufactured in Shiregreen is also hidden in the dust of history, but fork making did come to this small village to the north east of Sheffield, no matter how difficult this might be to visualize now, and the story of Shiregreen forks deserves to take its place among the history of Sheffield's cutlery.

Scattered through the village, attached to or built near the cottages, stood small workshops where father and sons worked together, the 'little mesters' of their trade. Some of these buildings can still be seen today, although often radically altered. There is one next to Mrs. Green's delightful cottage, 31 Oaks Lane, in which there used to be three hearths for fork making. There also used to be a Penny-farthing bicycle there too. Another fork shop stood further down the lane. It is a fine and unusual two storied fork shop, now a house, where the last forks to be forged in Shiregreen were produced by the Oxspring family. They ceased production only 17 years ago. In the archives at the Cutlers' Hall the Oxsprings are mentioned as early as 1772 as fork makers, and again in 1791, but as working in Ecclesfield - although Shiregreen was part of Ecclesfield then. The Oxsprings made three and four pronged personal forks as well as two tined carving and serving forks.

On Pear Tree Lane near the Co-operative Cleaning Department stands an old fork shop where steel used to be forged. In the yard behind the houses on Bellhouse Road to the north of Hatfield House Lane also stands a workshop and the site of another. Across the Lane on the other corner stood several more workshops - the entrance step of one can still be seen, and just beyond the Methodist Church across Winkley Terrace, stood two more. The base plate of a drop hammer was recently unearthed here during demolition of the adjacent cottages.

The last surviving hearth, looking as if the owner had only just stopped work, stands near the farmhouse of the recently deceased Mr. Hedley Challoner at 141 Hatfield House Lane. The workshop is getting somewhat dilapidated but the hearth, hearth stone, bellows and several implements still bear witness to the work carried on there. A year or two ago Mr. Challoner explained the method he used to make forks:

"First we take a strip of steel about 7/16th inches thick and form the tang that goes into the hand. Next thing we form the shank between the bolster and the prongs and then we cut an inch and a half off to form the prongs. Then we put the shank in a pair of tongs - what we call driving-up tongs - to form the bolster. Then we put a punch on it, with a hole in, over the tang, and hit it to flatten out the bolster. Then we next forge out the piece of square metal which was left to form the prongs. Next thing you have a pair of what we call "prints" and one man hold the fork and another man keeps hitting it to make the bolster a good shape. Now it is ready for the other end. The other end is laid on a die under a drop stamp which puts the fork into shape. Then there is fashers to be cut of by a cutter. Then it goes under another cutter to take the middle out. Next the prongs are opened out to the required width you want them. The next process is putting into final shape and hardening and tempering it. Then the forks are sent to the grinders wrapped up in grosses."

Associated with fork making was of course fork grinding. Mute witness to the role of the grinder are the several grindstones which can be seen set in the stone walls near The Hollies in Nethershire Lane and elsewhere. These stones could be turned by hand, treadled by foot or turned by water power. Mr. Tom Rose who lived in the shop at the corner of Bellhouse Road and Hatfield House Lane used the treadle method, while at Butterthwaite the wheel was turned by the water of the Blackburn Brook. Hearsay has it that his was Sheffield's first water wheel and fortunately, the outline of the dam is still visible. At the time there was not a protective guard around the swiftly moving belt round the large wheel.

It was very interesting watching the fork maker at work. Children would often stand in the doorway of the workshop til they had to run to school so as not to be late.

In one corner of the workshop could be seen long thin bars of steel, fine coke in another. The fork maker, with his left hand moving the large handle of the huge bellows making the coke in the forge glow more brightly as the air rushed through, would take with his right hand a piece of steel in a special holder and plunge one end into the red-hot cokes. Bringing it out white-hot some time later, he would hammer it on his anvil, flattening it and reheating it before he put it in the die-stamp. These dies were often self-made, and a few of them still remain in the district. They are moulds or patterns, one for the anvil and one for the drop-hammer, which was skillfully worked by one foot in a stirrup-like attachment fastened to a rope. Large stones associated with the drop-hammer can still be seen at the corner of Winkley Terrace.

Backwards and forwards went the piece of steel now slowly taking the shape of a fork. A special piece of sharp-edged steel was hammered between the prongs (this first condition was called the 'mood') an shining bits of hot metal would fall in heaps around the anvil or stithy. Then the fork was plunged into a tank of water with an exciting sizzle, steam rushing upwards and the process was ended with the fork being flung onto a heap at the side and the whole process would start again - the piece of steel about to be forged three times before it would be a finished product.

Fourteen to the dozen was standard practice and the piece-work rate of payment was based on this number. But the practice was not, as people think, to enable the buyer to get two more articles over and above the usual twelve for nothing. He would pay for the extra two forks in the case of wasters.

[Courtesy of : Bryan Woodriff (Professor) ]

More Sheffield History

Sheffield Indexers, Sheffield History

Sheffield Indexers collection of links to historical Sheffield including; Sheffield History, Laws & Acts, Living & Working Conditions, Historical Land & Buildings, Sheffield Flood and War Memories.

Sheffield Indexers, Other Historical Info

Sheffield Indexers collection of links to more articles of interest relating to Sheffield including; Sheffield Stories, Newspaper Articles, Editorials & General Interests, Sheffield Rhymes Etc, Cherished Sheffield Family Memories, Recipes of Olde Yorkshire, Old Sheffield Picture Post Cards and Yorkshire Expressions.